Making a shape tool for GIMP: Part One

From when I was very young, I have been enamoured by desktop software. I still remember when I first started using a computer in the early 2000s.

I was under 10 years old and everything was new. Pictures loaded procedurally and you could watch the page load one element at a time, the framing and scaffolds of the page resizing as content loaded and filled ever-expanding spaces. There was a sense of wonder as the page loaded then finally it all came together as a finished product. Almost like a delicate dance. Things trading sizes with other things, collapsing and giving way. It was almost as if you were inside the mind of the web-designer, cobbling together the completed page from disparate components. Components building haphazardly like a shanty town.

Ah, what a fantastic time

It was somewhere among the columns of web content. CSS grids that were strewn together with meticulous but fragile craft, that I first began pulling these things apart. Alongside 1-pixel-wide images from columns that managed to make sites juuust legible on Internet Explorer.

Like many kids of the era, I found the Right Click -> Save Page As shortcut. Just like that, I could have the website on my own computer, ready to view even when Mum was on a phone call! (Back in those days, on our DSL connection, a splitter was required for the phone. As was quite common for some reason, the splitter was never installed by our internet provider, and none of us knew better to add one. For many children of that era, the idea of needing to get a dose of internet in before a phone call shut it off became a point of commonality).

It wasn’t long before these HTML files and directories with images were strewn across the desktop of the family PC. And not long after that, I discovered that they were editable. I could open them right up in notepad.exe and change things! At first, things broke every time I tweaked something. Resources online were scarce about web standards at this time, with w3schools.com operating probably the best resource outside of books. Most was learned through experimentation, tweaking the source code little-by-little and seeing where things ended up.

By this point you may be wondering where I am going with all of this. Surely he has a point, surely there is a lesson to the proverb.

That much is true. Because I’ve been feeling again like that kid recently. As I’ve gotten older, and put on my big boy boots, and become decidedly professional about things, the effect of realising just how much exists becomes ever more all encompassing. I’ve been performing the same process again, feeling the computer archaeology whisk me away into a world slightly older than I am. Because I have been staring at the source code of GIMP.

Me and the GIMP

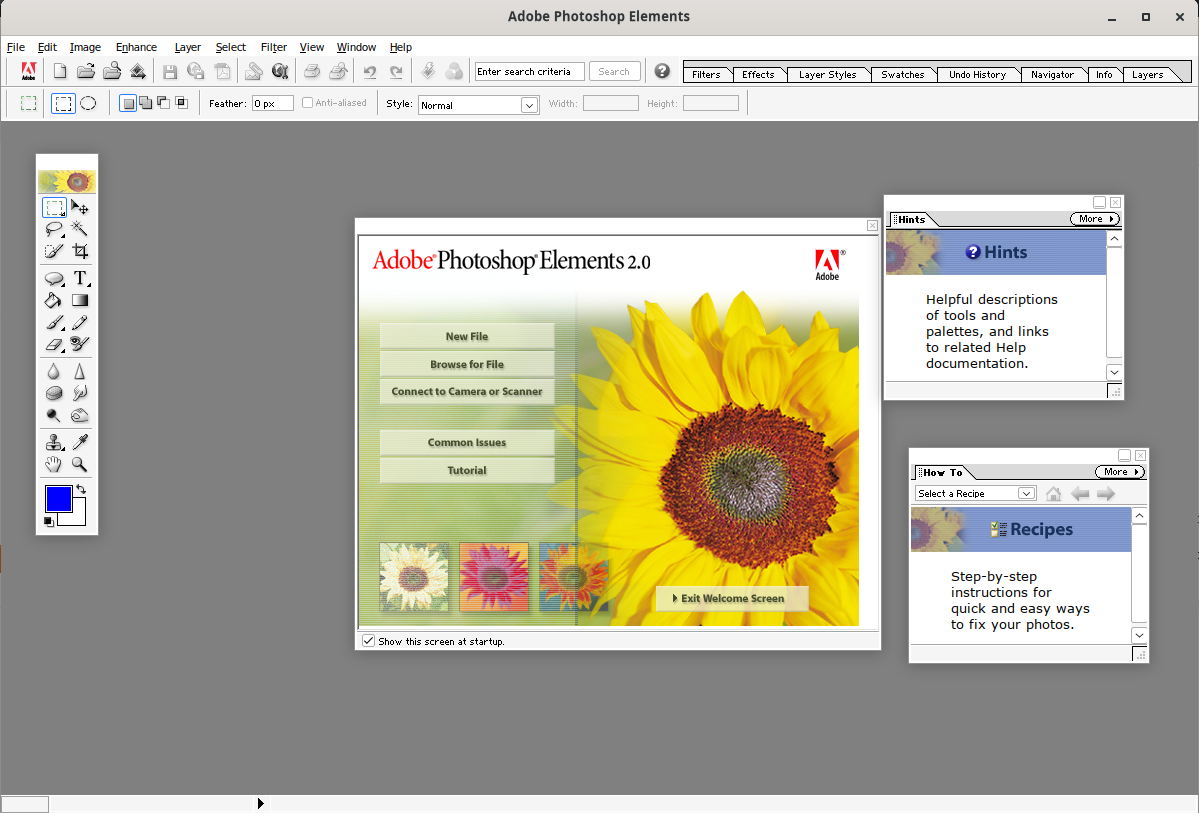

Editing text files is all well and good, and I could change the text and even figure out how to move things around. However, eventually I wanted to change how the pictures looked. After all, early web design used pictures for a great deal. My (only) tool at the time was Adobe Photoshop Elements 2.0

Remembered fondly by the big sunflowers

The software itself came bundled, free with a DSLR that my Dad had bought. It was promptly installed on the family PC and used by all of the kids. For me, it was everything I could have asked for. I could paint, I could draw shapes. If I was getting very advanced, I could even add a new layer. Any more functionality was inconceivable to me, and I’m not sure what I would have even done with it. The restrictions were empowering. I’m not sure I even knew more was possible. All of us would sit down with a goofy photo of one of us, then manipulate it bit by bit. Making liberal use of the filters dialog (especially the liquify tool)

At the time I couldn’t even concieve of a tool similar in breadth to Adobe Photoshop, Elements had all that I needed.

Around this time I discovered the GIMP. It was a strange software to me, its many oddities and peculiarities about the way the workflow worked seemed utterly foreign to me. The feeling I had of picking up the software and immediately knowing how to use it, like I had with Elements at only 7 years old was not my experience, now a freshly minted (Linux Mint!) 12 year old. The old family computer had been gifted to me and I wanted nothing more than to install my new favourite operating system on it, Linux. As it did not run Elements 2, so GIMP it was.

Over the years, the GIMP became second nature to me. It’s oddities and peculiarities began to make sense in my mind, and I began preaching a similar rhetoric to others around the way it was designed. I believed the fact that the user interface was just different to Photoshop, not foreign to new users. Note that this is, in particular, not a criticism of GIMP. Quite the opposite in fact, I just think on the sliding scale between usefulness for beginners and utility for power users, the GIMP favored the latter end of the spectrum.

Not pictured: The full photoshop sits on a separate axis

The feature set of GIMP has more in common with the full version of Adobe Photoshop than with elements, but for me, it only needed to perform the same function. Of the functions in Elements, everything was included. All features but one

The damn shape tool

In an odd twist of fate, today the situation is different. Photoshop Elements 2 no longer runs under modern version of windows, but funnily enough it runs fine under Linux using a tool called wine.

It's so beautiful

Note: This is also thanks to archive.org. The efforts there to preserve software are greatly appreciated

Using Elements under wine is surprisingly nice, and it’s easy to gain an appreciation for the no-nonsense app design that pervaded the early 2000s. In a desktop paradigm that seems to have evolved only horizontally, with ever-increasing layers of visual clutter and shifting of ideas, nothing seems to have made the overall paradigm shift in the deskop space. We still deal with the same set of buttons, radios and docks.

Using Elements under Wine, we can draw shapes just fine. We can even perform boolean operations on them!

The interface of Elements 2.0 has a lot in common with modern Photoshop. If something isn’t broken, why fix it I guess.

So why does a 20 year old version of a consumer-grade piece of photo editing software have a feature that a markedly more capable open source software of today has yet to produce? The truth is that there are a number of reasons. All of them are very valid. I have not been historically involved in the development of GIMP, but (somewhat remarkably) the issue tracker for the project stretches back some 25 years.

Why was it never done

In a fascinating treasure trove, the original issue #12 is still present and unresolved. It is open for any developer to come along and attempt, and even suggested by @Jehan as a good first feature for well-seasoned developers. To clarify, it isn’t a hard feature on the absolute, but doing it right and in-line with existing features is non-trivial. Again, I am no expert. From a cursory glance at the comments on the original, the reasons behind the delay seem to come down to three main reasons.

The GIMP is a bitmap editor

Adding vector features to a bitmap editor can always be a hard sell. It has everything to do with the simple sliding scale I showed above. The shape tool is a handy feature, but not necessary for the intended use cases of GIMP. Eventually, GIMP went some way towards having vector features with the Path Tool (Internally, it is named

GimpVectorTool), but features like the path tool directly serve bitmap editing by allowing the user to easily create bezier masks of pixels. Fundamentally, the idea of a shape tool steps into specifically drawing software territory, where open-source is already well represented by the likes of inkscapeVector layers (Doing it right)

Gimp has support for vector data, in the form of paths. However, these can’t yet be leveraged non-destructively. A feature like this would require something like the GSOC 2006 vector layers patch being applied. Without these two features coming together (the shape tool AND vector layers), the addition of a shape tool that only edits vector data would serve only to confuse at best.

It’s intimidating

Ultimately, the work required for adding a shape tool and fixing the proposed vector layers patch are achievable by single developers in isolation, but the entire task of adding a shape tool alongside fixing up the orphaned vector layers code is fairly monumental.

Adding a shape tool to GIMP

I am but a small cog in a very rich and delicate machine when it comes to the GIMP source code. I have a fairly intricate understanding of how GObject and Gtk works from pervious experience, however my understanding does not even come close to understanding the monumental amount of work that goes into something like GIMP. It’s best to start at the beginning and work from there, along with seeing where similar attempts came to.

Prior work

Way back in 2009, interest in the patch reached a level where a number of students designed the tool in teams. There are some very good ideas here, and all of the proposals are well and truly worth a read. Since this has been done, many facilities related to shapes have been added to the GIMP codebase as well. At this point, the work of adding the shape tools will not actually involve any design passes on widgets to define the shapes, as these already exist for the selection tools.

A note about looking at the source code of GIMP; there is a particular spiritual moment when looking through the code and you see something like Michael Natterer, 20 years ago. I am painfully aware that this software is older than me. I would do well to respect the software and its architecture, and touch as little of what already works amazingly well as humanly possible.

Planned approach

This is the part that required some analysis. GIMP is an extremely well designed piece of software, and has become especially so after the GTK 3 port. In particular, tools use the excellent GObject type system, with the ability to inherit from each other. GIMP Already has GimpVectorTool, which we now know as the path tool.

GimpVectorTool is great. It’s a tool that allows us to move and edit things that are called GimpVector. Currently, only one can be edited at a time, however there’s no reason to change this paradigm for the moment. Many tools in GIMP follow this paradigm, they accept a certain type of GimpItem that can be attached to a GimpImage. Currently, we can set GimpVectorTool to edit any set of GimpVectors that are in the current image.

Separated out in GimpVectorTool code are a whole number of functions that are attached via GObject signals to a widget created by GimpToolPath that exists as a member of GimpVectorTool.

The plan is to separate these functions to a new tool that inherits GimpVectorTool (it isn’t going anywhere), called GimpPathTool. We then can create GimpRectangleTool, GimpEllipseTool and GimpPolygonTool as multiple sub-classes of GimpVectorTool, which delegate their respective functionality setting and modifying their respective shapes in the current GimpVector. Moving and editing the vectors will stay the same, and being in a respective shape widget can denote editing those shapes.

Another thing we might be able to figure out later is if editing functionality should be common. IE: The correct tool is selected when a portion of the respective shape is selected.

The other thing that will have to be done, is GimpVectors will need to support shape primitives of some type. This can be done a number of ways. The shapes could be stored as paths, then metadata pointing to the primitive each path is based on stored alongside them. From my perspective, this would be a fragile solution. The current plan is to store primitive shape data inside GimpVectors as well. The gimp save file will then be updated.

Once this is all done, we’ll be able to define vector paths with primitives. When combined with the vector layers patch I mentioned earlier, we will have a complete solution for primitive shapes in GIMP.

Note: The class names aren’t final, maybe I’ll add Shape to them?

Starting at the beginning

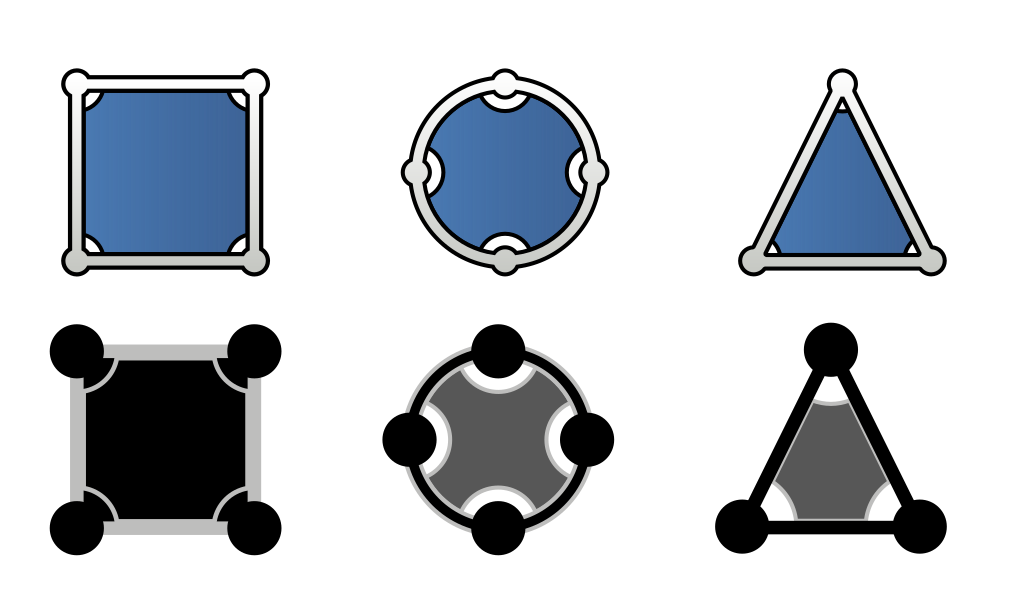

Because it’s exciting, I started with some simple icons. I’ve thrown some together in Inkscape, in both the colour and symbolic themes.

Some brand new symbolic and colour shape icons

I’ve separated GimpVectorTool out into GimpVectorTool and GimpPathTool. I have started on the first of the shape tools, GimpRectangleTool. It will use the same controls as the GimpRectangleSelectionTool uses, so the GUI part won’t even be that bad!

I’m beginning to add fields for primitive shapes to GimpVectors so that we can save our data to them from GimpRectangleTool. The feedback cycle of working like this is very rewarding, with a build-test-build cycle developing as I familiarize myself with the very well-structured source tree.

To be continued

I’ve started work on this in my own branch here. As I progress, I’ll definitely get in contact with the GIMP team and potentially send them this blog post. I’m sure there will be issues with my approach that I’m not aware of and they will be corrected. This is, after all, the spirit of open-source software! I’ll definitely learn something!